By Carrie Cox

The hot contender to supplant a gas export industry fuelled by fossil fuels is clean hydrogen, but research is needed to bring costs down.

There’s a distinct Field of Dreams whiff about WA’s nascent hydrogen export industry. As governments race to incentivise development and industry stumps up the cash for vital research, there is still the question of if we build it, will they come?

More specifically, as resources expert Professor Mike Johns puts it: if we successfully replace the state’s carbonised energy production with clean hydrogen, will buyers like Japan and Korea be happy to cover the considerably more expensive costs of doing so?

It’s a tricky question but arguably a redundant one, according to Professor Johns. As research director of UWA Future Energy Exports Cooperative Research Centre, Professor Johns says he doesn’t see a more viable alternative than clean hydrogen to replace WA’s 390-million-tonne-a year LNG export market – unless we’re happy to keep burning fossil fuels.

And the potential to reduce the production costs of clean hydrogen is significant. Indeed it’s an engineering challenge that has partially reshaped UWA’s Fluid Science Resources and Research Group, which Professor Johns also co-leads with Professor Eric May. In recent years, the group has pivoted to address the many new questions being posed by industry and government about renewable energy production.

“In oil and gas, it’s pretty well established what works and doesn’t work and so you’re looking at fairly minor improvements only being possible,”

Professor Mike Johns.

“However, when you’re talking about renewable hydrogen, there are a lot of unknowns and lots of opportunities for optimisation. A major driver for our research is ultimately to make it more cost- effective and therefore more acceptable to the public.”

One way of storing and transporting hydrogen at high density is in liquid form, however the process involves what Professor Johns dubs “weird physics”. The gas has an extremely low boiling point, so to liquefy it (for export) requires highly specialised equipment and energy-intensive cryogenic cooling systems. It’s a very expensive process (currently three to four times more costly than producing natural gas) and requires an enormous amount of energy.

“It’s where physics meets engineering in a rather bizarre way,” Professor Johns says. “If you just liquefy hydrogen, it will boil off immediately, so we’ve got to convert it first and we’re doing a lot of experimental work and modelling right now to reduce the cost of that process. We’re also looking at using mixed refrigerants, we’re doing some exciting work with magnets, and we’re also looking at what happens at the other end of the process – regasification of the hydrogen at the export destination.”

The latter project, dubbed ‘Cold Energy’, attracted $605,000 in Australian Research Council funding in 2022.

Professor Johns says while governments are now demonstrative in their pursuit of a clean hydrogen export industry — WA launched its Renewable Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap in 2019 and has since greenlit several major development projects — the first domino is yet to fall in terms of major export activity. When it does, though, the State needs to be ready to meet potential demand head on.

“The distinct advantage for us here is that we’re already a major gas exporter with established markets and a lot of the research we’ve already done to make the LNG export market more viable has parallels with liquefying hydrogen,” he says. “So the research we’re doing now is both very exciting and very important.”

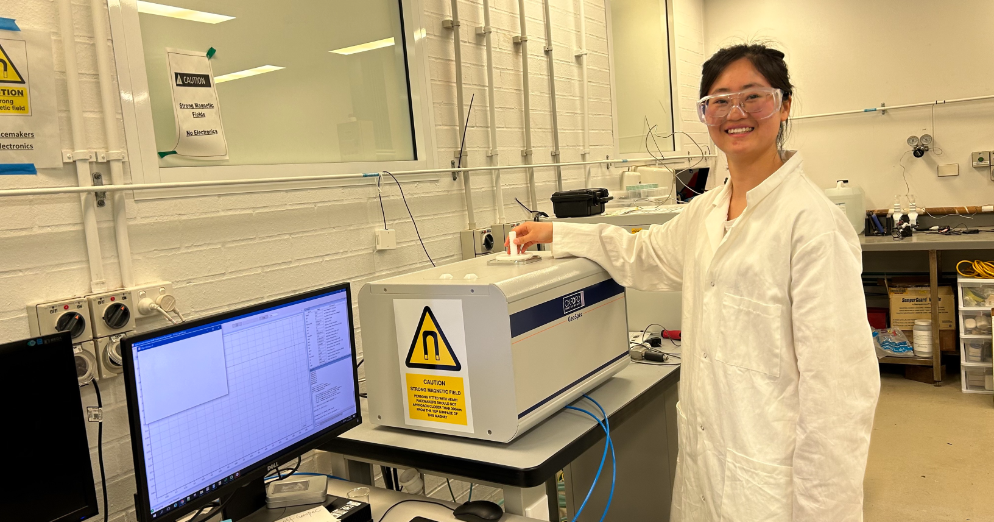

PhD candidate Shuang Dong characterising porous materials used for gas separations.

While exportable clean hydrogen is the primary focus for Professor Johns and his research colleagues, there are domestic opportunities too. “A lot of our own energy needs can be met with a mixture of solar and wind, but they are intermittent and so the back-up is likely to be gas peakers, (natural gas-powered plants run only in times of high demand) but there will be a small role for hydrogen as a back-up mechanism in certain locations,” he says.

“And then there are the industries that are hard to wean off hydrocarbons — typically any kind of processing that needs high temperatures and is hard to run off electricity. Hydrogen could also play a role in long-distance transport, marine transport and aviation. It won’t dominate but it would have a piece of the pie.”

Read the full issue of the Summer 2023 edition of Uniview [Accessible PDF 15Mb].