This is an article by Professor Joakim Goldhahn, Rock Art Australia Ian Potter Kimberley Chair from the School of Social Sciences at The University of Western Australia, Professor Paul S.C.Taçon from Griffith University, Senior Research Fellow Andrea Jalandoni from Griffith University, Adjunct Fellow Luke Taylor from Griffith University, Associate Professor Sally K. May from the University of Adelaide and Danek Senior Traditional Onwer Kenneth Mangiru originally appeared in The Conversation on February 23.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

Arnhem Land rock and bark paintings have fascinated people across the world since the early 1800s. Rock art was first recorded by Matthew Flinders and his onboard artist William Westall at Chasm Island in January 1803 while they were circumnavigating Australia.

In the early to mid-1800s, there was interest in Arnhem Land paintings on sheets of bark used to form hut-like shelters by visitors to Port Essington. In the late 1800s, some visitors to Arnhem Land collected barks for museums.

The names and stories of the individuals who made most Aboriginal rock art and the earliest collected bark paintings are not known.

We have recently begun to address this. We have identified various artists who made early bark paintings and recent rock paintings.

Today, in Australian Archaeology, we announce the identification of another artist, Majumbu, also known as “Old Harry”.

Painting in Oenpelli

From 1912, anthropologist Baldwin Spencer and buffalo-shooter Paddy Cahill collected 163 bark paintings at Oenpelli (now Gunbalanya), Arnhem Land, near present-day Kakadu.

We used Cahill’s and Spencer’s notebooks and letters that identify a clan patriarch “Old Harry” as an artist who painted one of the spirit bark paintings and another, now missing, with three fish.

By scouring ethnographic records and constructing genealogies, we realised Old Harry’s Aboriginal name was Majumbu, and he also made rock paintings.

We analysed Majumbu’s characteristic art style from the known spirit bark painting and looked for evidence of the same features in the rest of the collection, identifying a further five paintings as well as another overseas.

With Aboriginal research partners, including two of Majumbu’s great grandchildren, we reviewed the paintings held in the Melbourne Museum and identified some of Majumbu’s known rock paintings to confirm him as the artist behind six of the works in Melbourne Museum’s collection of barks, and a seventh in the Museé du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, in Paris.

A majestic sight

Cahill established Oenpelli near the East Alligator River as a base camp settlement in 1910, employing Aboriginal people for buffalo hunting and agriculture.

Spencer first encountered bark paintings in July 1912 during his two-month stay with Cahill at the Oenpelli homestead. Spencer described in his notebooks the very positive impression the barks made on him and also commissioned a series of works from some of the most skilled artists.

Majumbu and his family were Kunwinjku language speakers from an area east of Oenpelli. He and his six wives and several children were frequent visitors to Oenpelli.

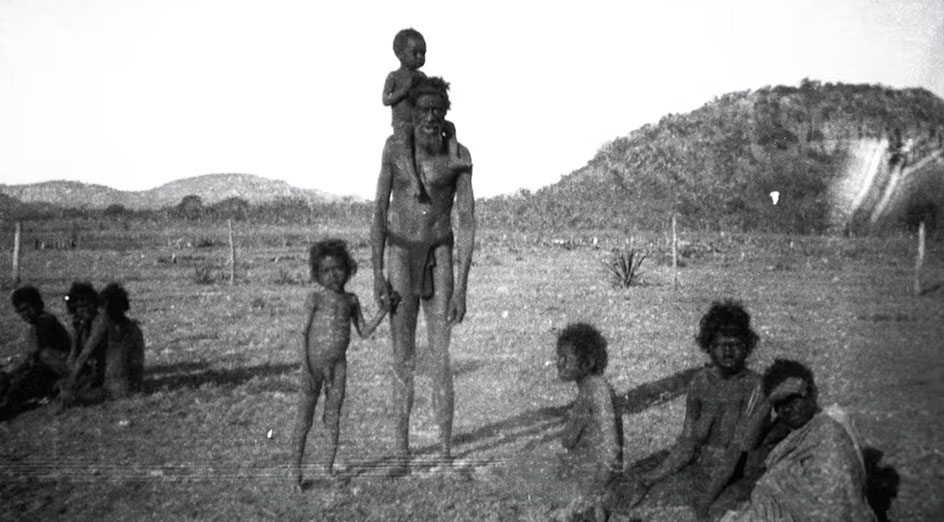

Majumbu was described by visiting journalist Elsie Masson in 1913 as a “grey-bearded warrior” who

was a majestic sight, as he stalked, tall, gaunt, and solemn, across the yard, with his small son and heir perched high on his shoulders.

Image: Photograph of man said to be Old Harry (Majumbu) and his family by Elsie Masson. Photograph courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum, object 1998.306.60, 1913

Image: Photograph of man said to be Old Harry (Majumbu) and his family by Elsie Masson. Photograph courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum, object 1998.306.60, 1913

Distinctive features

Majumbu’s artwork has distinctive stylistic features.

The bark paintings we identified all have similar hatch infill (rarrk) which features gently curving parallel lines of varying thickness. This is characteristic of Majumbu’s style, but not of other bark or rock artists from the area who painted parallel hatch lines of uniform thickness.

Some of the human-like figures in Majumbu’s paintings have an extra digit on their hands. He also often painted an X on hands and feet of human-like and some animal figures.

Image: Kulunglatji (Kunwinjku) bark painting of a spirit called Mununlimbir. Photograph courtesy of the Melbourne Museum, object 019921, registered on 22 September 1914; object size is 1.845m by 0.830m

Image: Kulunglatji (Kunwinjku) bark painting of a spirit called Mununlimbir. Photograph courtesy of the Melbourne Museum, object 019921, registered on 22 September 1914; object size is 1.845m by 0.830m

When eyes are shown, they are on stalks or are represented as rectangles. Human-like figures have diamond patterning for some of their infill and there is a central division of limbs and bodies.

The largest bark in the Melbourne Museum’s Spencer-Cahill Collection is dominated by a painting of a crocodile that measures 2.94 metres by 1.03 metres. It is almost identical to a rock painting known to have been painted by Majumbu in a rock shelter where his family regularly camped.

With Gunbalanya community members, we relocated his crocodile rock painting in September 2022. The crocodile is significant because of the key role they play in regional ceremonies.

As with the spirit being paintings, it reaffirms Majumbu’s connection to his traditional land.

Priceless heritage

We are indebted to the early bark painters of western Arnhem Land for creating such an extraordinary assemblage of paintings, and to Baldwin Spencer and Paddy Cahill for recognising their importance and having the foresight to collect them at a time when Aboriginal art was not valued by outsiders.

We are now able to learn about some of the Aboriginal artists behind this collection, their families and their lives, adding new life and significance to these early bark paintings not only for interested people across the globe but also for the artists’ descendants, most of whom still live at Gunbalanya (Oenpelli) today.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.