This article by Professor Jane Lydon FAHA, from UWA's School of Humanities, originally appeared in the Australian Academy of the Humanities on 23 August 2023.

Please note that this article contains distressing imagery and photos of people who are deceased.

Wednesday 23rd of August is the UNESCO International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. It aims to ‘inscribe the tragedy of the slave trade in the memory of all peoples’ and reflect on its history and legacies in the present. The date marks the start of the 1791 Haitian Revolution, a key moment in the struggle against the transatlantic slave trade, which transported up to 12 million enslaved African people mainly to the Americas.

Great Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 and outlawed chattel slavery in 1833, but in the United States slavery only ended after the American Civil War, and persisted elsewhere - notoriously, Brazil only enacted emancipation in 1888.

Celebrating the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, however, has blinded us to important differences between historical and contemporary forms of exploitation. Within the Western imagination the powerful and emotive anti-slavery campaign waged in Britain before 1833 has indelibly embedded the imagery of chattel slavery - shackled black bodies, brutal slave-masters wielding whips, and white abolitionist heroes.

The binary of ‘enslaved’ or ‘free’ continues to have great cultural power. These historical stereotypes obscure our understanding of the ways in which abolition generated a global shift to indentured labour migration as a means of securing cheap, docile, usually non-white labour.

Recent research has begun to analyse the links between Britain’s Caribbean slave system and its newer settler colonies, considering abolition in terms of the wider imperial reorientation connected to the development of global industrial capitalism.

We have forgotten that British slavery was in full swing for 45 years after New South Wales was founded.

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 established a system of apprenticeship, and granted £20 million in compensation to the former slave-owners, to be paid by British taxpayers via a government loan – shockingly, this was only acquitted in 2015. The Legacies of British Slavery (LBS) database, hosted by University College London, became publicly available in 2013, allowing the records of those compensated for the loss of their ‘property’ after 1833 to be searched online by a global community. Through the lens of the compensation awarded after abolition we can trace the movement of capital, people, and culture from Britain’s slave system to the Australian colonies, opening our eyes to the deep interconnections between the two systems.

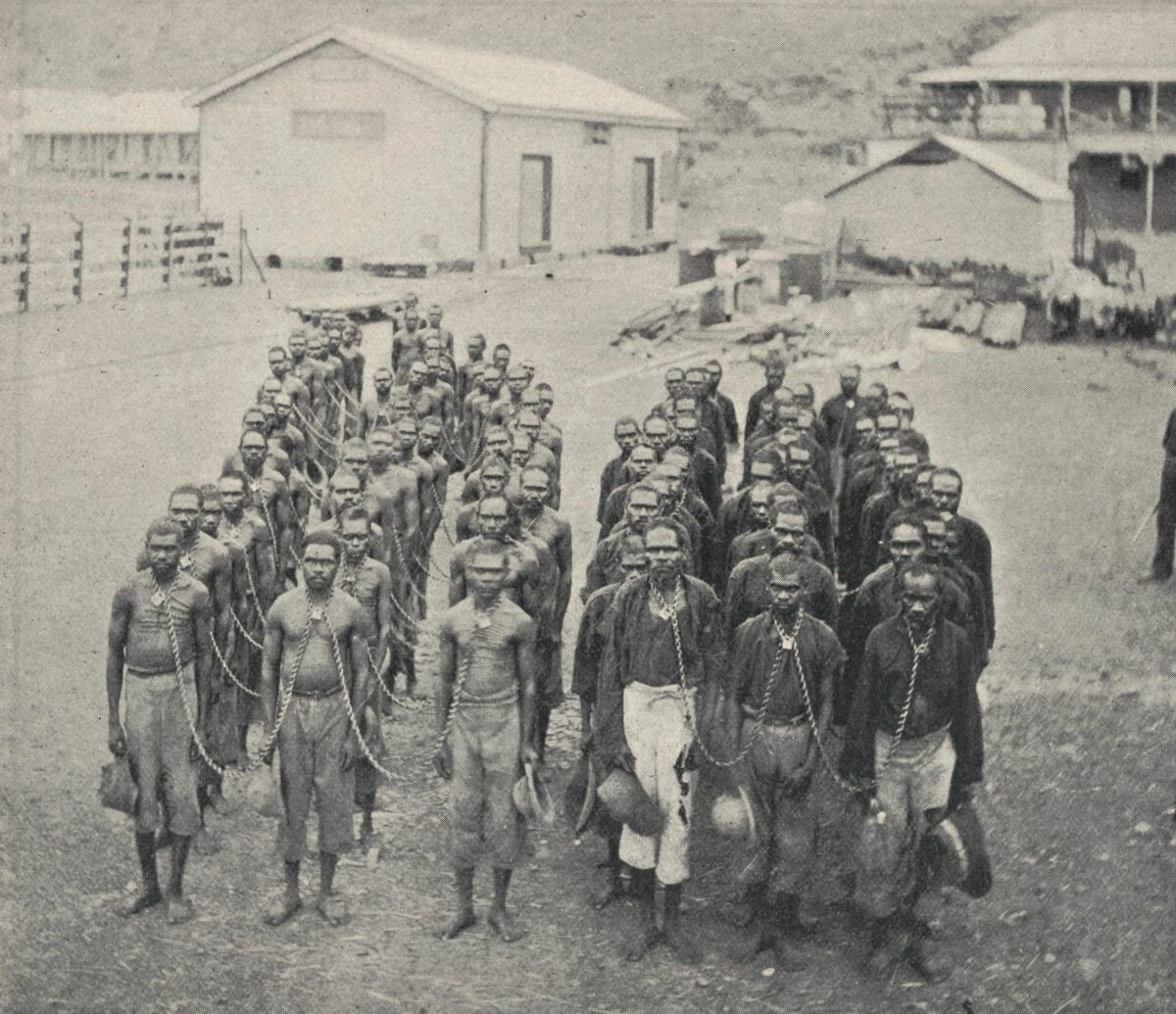

Image: Aboriginal prisoners in neck chains. Elders in the Kimberley are pleased for this image and its history to be shown according to the author.

Image: Aboriginal prisoners in neck chains. Elders in the Kimberley are pleased for this image and its history to be shown according to the author.

The LBS identifies more than 230 individuals with links to the Australasian settler colonies - a number that continues to grow as the database is updated. Exploring their life stories and kinship networks reveals that many from Britain’s slave system moved to Australia: these included planters, managers, absentee landlords and their extended families, but also the formerly enslaved. Leading civil servants, including governors and law-makers, also had strong financial and professional connections to Britain’s Caribbean colonies, and applied their experience to Australian circumstances - and to First Nations people.

In Western Australia, for example, Noongar people were valued for their labour from the early days of colonisation and were subject to violence that maintained racial hierarchies across the British empire. In 1834 the 21st Regiment of Foot led the most intense phase of violence between colonists and Binjareb Noongar, climaxing in the infamous 1834 Pinjarra Massacre. A decade earlier in 1823, soldiers in the 21st Regiment of Foot played a prominent role in quelling the landmark Demerara slave rebellion, in what is now Guyana. The common use of legal violence reveals continuities between British slave and settler colonies.

WA Supreme Court Chief Justice, Archibald Paull Burt (1810-1879), was awarded slavery compensation for three sugar estates in St Kitts. He founded a pastoral dynasty in the Pilbara and his son, Septimus Burt (1847-1919), became a proponent of the 1892 Aboriginal Offenders Act (Amendment) that sought to re-introduce flogging. Septimus argued ‘the only way of effectually dealing with all these coloured races — whether blackfellows, or Indians, or Chinamen, is to treat them like children … whip them. It is the only argument they recognise, brute force. … give them a little stick when they really deserve it, and it does them a power of good.’

Image: Sugar cane growing in the Perth garden of St Kitts-born Archibald Burt in 1862. Burt, a former slave owner, became chief justice of Western Australia. State Library of Western Australia 6923B/182.

Image: Sugar cane growing in the Perth garden of St Kitts-born Archibald Burt in 1862. Burt, a former slave owner, became chief justice of Western Australia. State Library of Western Australia 6923B/182.

Some of Britain’s most prosperous mercantile houses derived capital from the business of slavery, and extended their operations from the Atlantic to Australia. In the Port Phillip District, for example, as Zoë Laidlaw has explored, important pastoral ventures, including Niel Black & Co (est. 1839) and the Clyde Company (est. 1836) were founded on slavery wealth. In Queensland, Emma Christopher has revealed the involvement of sons and/or grandsons of transatlantic slave traders, Caribbean plantation owners, or both in the genesis of the sugar industry and South Sea Islander labour.

Both slavery’s defenders and its opponents were concerned to maintain a reliable labour supply after emancipation - so ‘systematic colonisation’, as envisaged by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, gained popularity not least because it explicitly sought to replace slavery with ‘free’ labour. In South Australia, founded upon Wakefield’s principles of land commoditisation, wage-labour, and forced migration, compensation paid under the 1833 Abolition Act was invested directly into many South Australian land purchases; four of the nine Colonization Commissioners appointed in 1835 were significant slavery beneficiaries. Tellingly, these mechanisms were also applied to the post-emancipation Caribbean colonies, especially those ‘newer’ sites with uncleared land such as Trinidad.

These processes shaped modern global geopolitics by commoditising land and labour, racialising freedom and citizenship as white, and creating forms of forced migration still evident today. Modern abuses may entail a range of exploitative practices, including human trafficking, forced labour, forced marriage, the worst forms of child labour, servitude, debt bondage, and the removal of organs. But even these terrible practices should be seen in the context of broader structures of exploitation inherent within the global economic system of neo-liberalism – and the history of the transformation from slavery to settler colonisation.

Jane Lydon is the Wesfarmers Chair of Australian History at The University of Western Australia. Her most recent book is Anti-Slavery and Australia: No Slavery in a Free Land? (Routledge, 2021) which argues that colonisation in Australasia facilitated emancipation in the Caribbean even as abolition powerfully shaped the Settler Revolution. She leads the Western Australian Legacies of British Slavery project. She occasionally ventures on to Twitter as @LydonJane

[1] Western Australia Parliamentary Debates, 29 January 1892, p. 398 (S. Burt, Attorney-General).

[1] Justine Nolan and Martijn Boersma, Addressing Modern Slavery (Sydney: New South Books, 2019); The Australian government uses the term ‘human trafficking and slavery’ to encompass the range of slavery-like practices contained within the Commonwealth Criminal Code Act, including servitude, forced labour, deceptive recruiting for labour or services, forced marriage and debt bondage. Australian Government, Attorney-General’s Department, Criminal Code Act (1995).