Bardi Jawi woman Erica ‘Roobaanjarn’ Spry has dedicated her career to improving the lives of Aboriginal people in Western Australia’s remote Kimberley region and beyond.

With her mantra, “As Aboriginal people go forward, so do I”, Erica has been pivotal in re-shaping diabetes research for all people, and especially Aboriginal people.

She was recently recognised for her work in this space with the 2023 UWA Vice-Chancellor’s Indigenous-led Research Award. This is a remarkable achievement and a testament to Erica's dedication and hard work in Aboriginal health research over many years.

.png)

Image: Erica Spry and UWA Vice Chancellor Prof. Amit Chakma.

Erica says it was family that inspired her to become a research officer with the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service (KAMS) in 2016, and later sharing her KAMS role with the Rural Clinical School of WA (RCSWA) in 2019 as a research fellow.

Working in the women’s space from youth to now a Kimberley Elder is a natural fit for Erica. She is well known to many throughout the Kimberley as a person who loves to give positive projects a go which result in community improvements.

“I was brought on originally to work on the ORCHID study which was initiated in the Kimberley. It is open to WA women of all ethnicities, but in my role, I was able to help facilitate Aboriginal mums’ involvement in a culturally safe way,” she explains.

The ORCHID study is a collaboration between RCSWA, KAMS and their member services, Diabetes WA and the WA Country Health Service. It aims to simplify the screening and management of high blood glucose (hyperglycaemia) in pregnancy.

“If you are carrying too much sugar glucose in your body as a pregnant mum, you are increasing your risk of problems when you give birth and of having Diabetes later in life,” Erica says.

“In my health research role, our team has proven that you can bring direct benefits through research. This includes sitting down and listening with mums, yarning about ways to manage blood glucose levels and reduce possible glucose-related harm to themselves and their developing baby.”

Pregnant Aboriginal women who have been diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and others with a history of GDM are now invited to assist with Phase Three of the ORCHID study. Erica and her colleagues are exploring culturally appropriate resources that can assist diagnosed GDM pregnant women to self-manage their diabetes in pregnancy.

.png)

Image: ORCHID project researchers Dr Emma Jamieson, Erica Spry and Michelle Thomas.

An old saying ‘prevention is better than cure’ rings true for Erica, and involving Aboriginal people in every stage of a health campaign for them is something she champions for this reason.

The ‘Be Healthy’ campaign is one such initiative that is designed by Aboriginal people and delivered by Aboriginal facilitators to prevent obesity and chronic diseases such as Diabetes in the Kimberley. The program features practical nutritional knowledge, cooking classes that can incorporate bush foods and seasonal knowledge, discussions of chronic diseases, stress management strategies, and exercise options.

Erica and her research colleagues also published a paper in the Australian Journal of Primary Health 2019 called ‘Understanding lived experiences of Aboriginal people with Type 2 Diabetes living in remote Kimberley communities: diabetes, it don’t come and go, it stays!’.

The paper highlighted the need for culturally relevant education and pictorial resources, the importance of continuous relationships with healthcare staff, lifestyle management advice that considers local and cultural factors, and the involvement of Aboriginal community members and families in support roles.

Kimberley clinical protocols on managing diabetes were revised in the wake of the paper. Today if an Aboriginal person is diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes or they have a change of medication, an Aboriginal health worker/practitioner is recommended to be present during these discussions, to support the patient through the process.

“The protocol change came about through direct appeal from remote community members and clinical staff who advocated the needs into forward planning and practice,” Erica reveals.

“When you’re an Aboriginal person coming into the health system, especially health research, it can be really confronting as the system seems set in old ways. Adapting to best practise is often challenging but I see the system changing, expanding, and involving more Aboriginal people in decision making, resulting in better health outcomes, tools, and systems.”

The development of culturally safe models of clinical practice has recently extended to mental health screening of Kimberley Aboriginal perinatal women, a new approach that Erica is especially proud of.

Co-designed with Aboriginal women and healthcare professionals, the Kimberley Mums Mood Scale (KMMS) tool is identifying women at risk of anxiety and depressive disorders through psycho-social ‘yarning’.

“The KMMS is about exploring social emotional wellbeing or what we Aboriginal people call “Liyan” our inner spirit, deep feelings. It’s a screening tool that was instigated by several clinicians because a lot of Kimberley Aboriginal women complained that the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was not culturally appropriate,” Erica recalls.

As one of the longest serving Aboriginal health research officers for KAMS, Erica has worked with many Elders and wise colleagues who have guided her career and supported her through many challenges. Research can be a long game with results taking many years to be generated and implemented.

.png)

Image: RCSWA Kimberley researchers from left, Erica Spry, Dr David Atkinson, Dr Emma Carlin, Prof. Julia Marley, Steve Pratt and Matt Lelievre.

Erica credits her family, Aboriginal Elders, and work colleagues with having the biggest impact on her research career to date and for keeping her focused on “real world” community outcomes.

“We work so well together as a team, with our research spanning regional and remote Aboriginal communities to sites across WA and Australia too,” she explains.

“Statistics always say life expectancy is against us, but I feel with the projects I’m involved with they do bring direct benefit back to community, mother and baby, and the extended family as well.

“A colleague and I have a special motto - ‘flourish’. We want to see all the women and children flourish. When you get the best beginnings, you are on the path for a better, longer life.”

Her family members including a University of Notre Dame Australia nursing mentor and a former Derby Aboriginal Health Service CEO have particularly inspired her to apply her knowledge and learnings, and to just be herself.

“I think it’s a wonderful space working with KAMS and RCSWA. The legacy of both organisations (40 years and 20 years respectively) and the Elders who have helped shape them. I’m excited about the future,” she says.

"I think I'll be like my late mother Djarrawan Dorothy Spry-Murphy and my late aunt godmother Maxine Armstrong (KAMS’ longest servicing chairperson), life-long advocates for Aboriginal people. I believe in my Aboriginal culture and its ability to heal."

Erica Spry

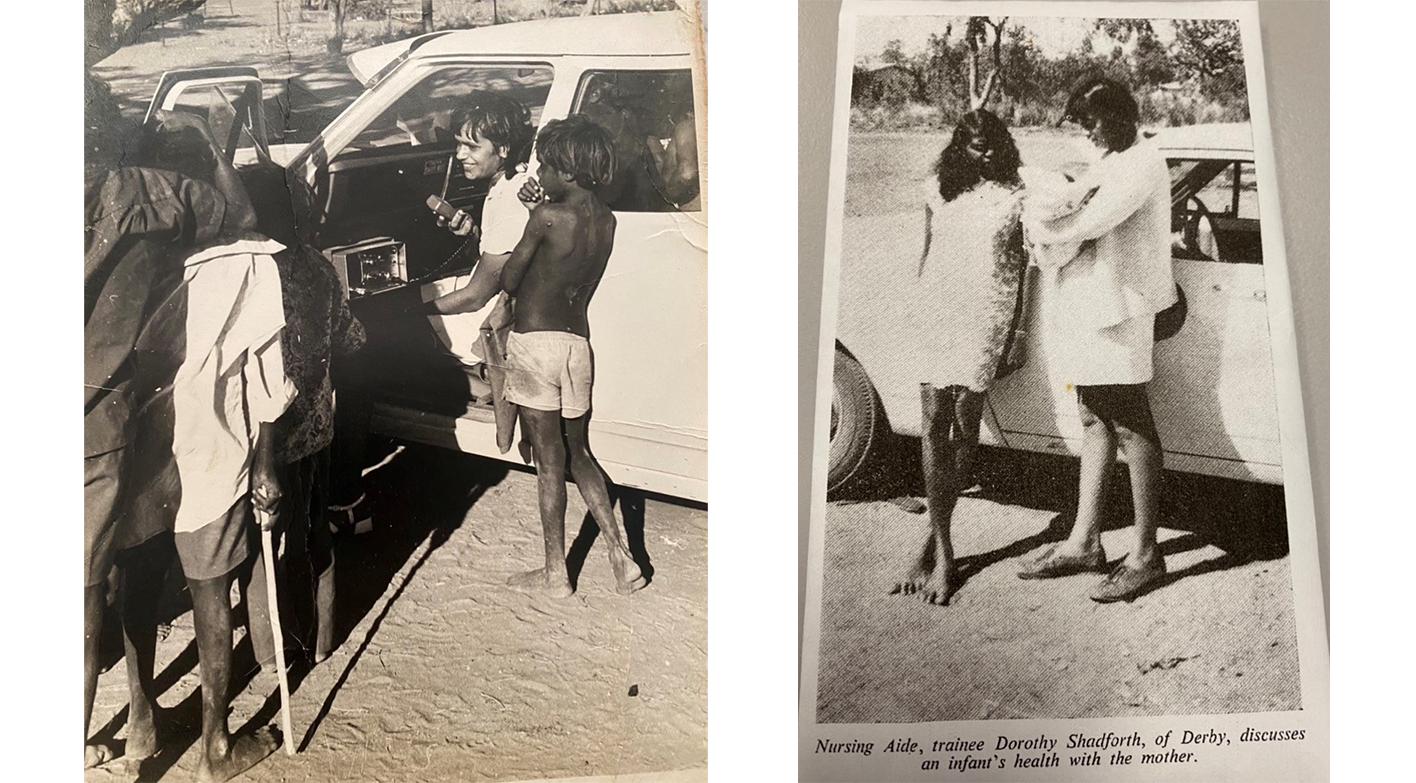

Image: Erica Spry's late mother Djarrawan Dorothy Spry-Murphy, a Kimberley Community Health Nurse

.png)

Image: Pictured left, Erica Spry's aunty mum Ina Kitching Shadforth - Derby Aboriginal Health Services board member on the KAMS board (now retired); and pictured centre, Erica's late aunt godmother Maxine Armstrong - KAMS' longest serving chairperson.